by Farah Hasan, September 27, 2022

Abstract

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has brought on unprecedented disruptions to global economies resulting in income loss and high unemployment rates that have disproportionately affected women. Existing research on COVID-19 and the economic effects of a pandemic on gender-based employment are limited, though rapidly growing, and a literature review providing a holistic overview is needed to advise and inform policymakers on important factors to consider when working towards reparations and economic recovery. Prior empirical work, particularly case studies, will be used for a primarily qualitative analysis, along with the presentation of some important statistics in regards to unemployment. Unemployment rates are exceedingly high for women compared to those for men in both developed and developing countries, with several female-dominated occupations (such as beauticians and cabin crew) being most severely affected by the pandemic due to closures and discontinuation of service. Policymakers should take several factors into account when working towards economic restoration such as a country’s status as developed or developing, type of occupation, and type of unemployment. Additionally, more focus should be given to implementing certain standard practices in promoting gender equality in work outcomes. Such policies will aim to revive employment while improving occupational gender equality in the long run.

Keywords: COVID-19; pandemic; unemployment; gender gap; developed/developing countries

1. Introduction

This paper seeks to discuss general trends in global unemployment rates after the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, to highlight patterns in the types of occupations most severely affected, and to evaluate potential changes in labor outcomes in regards to gender. As a novel occurrence, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted individuals and nations from a variety of different angles (such as healthcare, political standpoints, research and development, growing reliance on virtual settings, etc.) and has thus given rise to an immense amount of unknown territory for research. While extensive research is available on economic recessions, not as much is known about the unique impacts of a pandemic, especially as it relates to gender gaps. Most existing literature consists of case studies looking at unemployment rates and demographics within specific countries. It has been observed that the unprecedented disruptions to the global economies brought about by the pandemic in which diversified economies were providing job opportunities for women in different sectors has led to income loss and high unemployment rates. A literature review providing a holistic view of general trends in unemployment and relations to gender on a global scale (synthesizing the information from case studies on various countries) is needed to have a more comprehensive understanding of the true extent of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment and gender gaps. Understanding how the pandemic affected labor markets in both the developed and the developing worlds is crucial as governments continue to develop responses.

Most evidence used will consist of prior empirical work, such as case studies. The analysis will be mostly qualitative, but will provide valuable statistics and graphical data to highlight comparisons of unemployment rates in different countries and percentage breakdown of labor outcomes by gender. Current literature suggests that the pandemic has widened gender inequality in the labor market. Changes in the gap must be investigated in order to address the potentially growing inequality by enacting and strengthening policies to support women and prevent a possible increase in female unemployment and worsening of gender inequality. The purpose of the present literature review is to highlight various determinants of occupational segregation in regards to COVID-19, such that policymakers will have a clear understanding of factors to consider when formulating policy responses to alleviate the impact of the pandemic and take preventative measures against similar future crises. This will be achieved by discussing general trends in global unemployment rates after the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, highlighting which types of occupations and industries were most often and most severely affected by the pandemic, and evaluating the gender demographics of workers affected in both developed and developing countries across the globe. Failure to investigate this would leave governments and economists in the dark regarding any potentially exacerbated gender gaps due to the pandemic, obscuring the urgency of mitigating any harmful changes.

In the next section, I will present background on gender inequality and its connection to the pandemic. Section 3 is a literature review on COVID-19 and unemployment rates, types of jobs affected, and demographics of the worker population most severely affected. Section 4 synthesizes findings from the literature review and highlights salient determinants of occupational gender equality in regards to the pandemic, such as the status of a country (developed or developing) and type of occupation, that policymakers must pay heed to. Section 5 summarizes findings and discusses implications for COVID-19-related employment policies, limitations regarding scope of analysis, and recommendations for future research.

2. Background

Gender inequality is an issue in both developed and developing countries, with 18% of women having experienced physical and/or sexual violence in the previous 12 months (United Nations (UN), 2019). This percentage is even higher in developing countries. A greatly embraced solution to this issue is empowering women financially in finding productive employment opportunities (Dang & Nguyen, 2020). Despite these efforts, the gender gap in employment still exists to significant extents in countries around the world, both developed and developing. This occupational segregation also sheds light on the differences in types of occupations that women and men choose, differences in employment status, and differences in hourly wage. The gender gap is especially important to address, as this impacts lifetime earnings, retirement pension payments, and potentially the educational level and earnings of their children (Bächmann et al., 2022).

While there is extensive research on the impact of recessions on gender-based employment, knowledge on the impact of pandemics in particular on the gender gap is limited. Studies conducted after the Great Recession in the United States suggest that historically, women have suffered higher unemployment rates than men and that their employment tends to be less cyclical than that of men (Hoynes et al., 2012; Doepke & Tertilt, 2016). It is especially important to focus on gender inequality as a pandemic may differ from a typical recession; it more strongly affects sectors with high female employment shares and necessitates increased need of childcare for mothers due to school closures (Alon et al., 2020). Indeed, the pattern observed after the Great Recession is thus compounded by the effects of the pandemic, as some studies suggest that the negative effects of COVID-19 may have wiped out the global progress in gender equality and poverty reduction from the past 30 years (Sumner et al., 2020). The research that is available on gender-related impacts of a pandemic focuses mostly on developed countries, but even less is known about such impacts in developing countries, where gender discrimination is more prevalent and women are typically already worse-off than men in labor participation, job security, income, etc. (Hossain & Hossain, 2021).

3. Literature Review

In the following section, various notable statistics on unemployment rates due to COVID-19 in both developed and developing countries will be presented. Then, a closer look at the types of jobs most severely affected will be provided, followed by a breakdown of the demographics of individuals who work these types of jobs and were most affected by the pandemic and related governmental response policies. This section can be segmented into three major questions, which will be answered in the following literature review.

3.1 How has COVID-19 impacted unemployment rates?

Compared to the unemployment effects of recessions, the effects of the pandemic are staggeringly large in comparison. It is important to note the similarities between developed and developing countries in these skyrocketing unemployment rates, indicating that both types of countries were significantly affected and that a deeper look into the demographics of the workers affected is warranted.

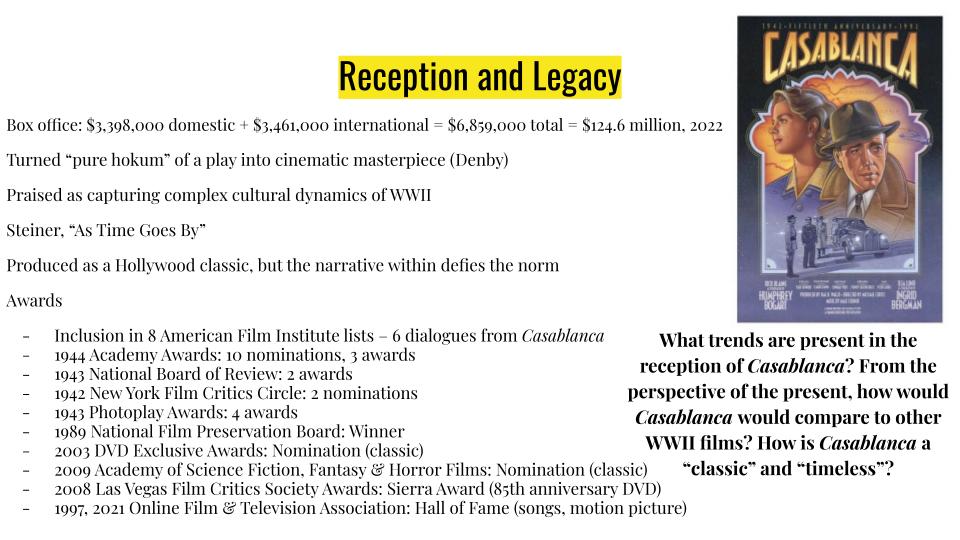

According to Figure 4, in the United States alone, the unemployment rate rose from 19.3% in February 2020 (the start of the COVID-19 recession) to 41.5% in February 2021 about 12 months later. Looking at unemployment rates during the US Great Recession, the unemployment rate began at 17.4% in December 2007 and climbed to about 23% within the same time span of 12 months (ultimately ending at 40.4% after 24 months) (Figure 4).

[Figure 4 here]

Thus, the spike in unemployment due to COVID-19 rather than the recession was significantly sharper and more profound within the same time span of 12 months, suggesting that the unemployment effects of a pandemic warrant urgent investigation (Bennett, 2021).

Different countries experienced these increasing unemployment rates in different patterns. Burns & John (2020) highlight unemployment rates from a more global perspective. While some countries experienced relatively constant unemployment rates throughout the pandemic (namely Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom), other countries experienced large and sudden spikes in unemployment similar to that in the United States (namely Canada, while Spain, Italy, and France experienced smaller spikes in unemployment) (Figure 5) (Burns & John, 2020).

[Figure 5 here]

Sweden, a country that will be discussed in depth later in this paper, experienced an overall increase in unemployment by 2.5 percentage points from February 2020 (one month prior to the onset of the pandemic) to July 2020 (5 months after) (Campa et al., 2021).

It is important to note that all of the countries discussed so far are developed countries, but the COVID-19 pandemic also had profound, if not even more significant, impacts on unemployment rates in developing countries as well. Prior to the COVID-19 breakout in Nigeria, Hossain & Hossain (2021) found that overall employment rates for women were lower than overall employment rates for men. It was noted that 80% of the sample Hossain & Hossain (2021) studied from Nigeria were employed before the pandemic. From March 2020 to May 2020, the early period of the pandemic, the employment rate dropped to 43%. Even after the pandemic broke out, the employment rate for women continued to be lower than that for men. Additionally, the overall likelihood of being employed dropped by 13% in Nigeria (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). Furthermore, as a result of the pandemic, a significant restructuring of the distribution of employees by gender in farming and business spheres occurred. The employment rate for women in business declined compared to male employment in business during the COVID-19 period (Figure 3c) (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). However, it is interesting to note that the employment rate for women in farming surpassed male employment in farming during the COVID-19 period (Figure 3b) (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). These findings will be expounded upon in the following sections.

[Figure 3 here]

3.2 What types of jobs were most significantly affected?

Several job spheres were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in both developed and developing countries, from aircraft operation to agriculture. By studying the types of jobs affected by the pandemic, valuable information about the nature of the jobs, worker skill sets/interests, and demographics can be determined.

In Sweden, some of the occupations that were most heavily impacted by unemployment were aircraft pilots, masseurs and massage therapists, cabin crew, and beauticians (Campa et al., 2021). Of these, the unemployment impacts range from 30.8% for aircraft pilots and related associate professionals (which was the highest) to 15.2% for beauticians and related workers (which was the lowest) (Table 1) (Campa et al., 2021).

[Table 1 here]

It is important to note that most of these occupations are service-based and typically require physical proximity, consistent with the expectation that they would be affected by social distancing measures necessary in reducing the spread of COVID-19.

In Nigeria, the agriculture sector typically hosts a large fraction of women and works as a buffer during economic shocks. Thus in the context of COVID-19, women engaged in agricultural work were more likely to keep their job, and the agricultural sector became an alternative employment option for women who were not already involved in it (Hossian & Hossain, 2021). This is consistent with the above finding that the employment rate for women in farming surpassed male employment in farming during the COVID-19 period (Figure 3b) (Hossain & Hossain, 2021).

3.3 What were the demographics of the employees affected?

After broadly considering general trends in unemployment rate due to COVID-19 and associated affected jobs, information on gender breakdown in these spheres sheds light on the disproportionately large impact of the pandemic on women compared to men. In doing so, it is important to consider the developed or developing status of a country as well as their response to COVID-19, as these also have implications on gender-based labor outcomes.

An overwhelming amount of evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened labor market outcomes for both men and women, but especially for women. Women are 24% more likely to lose jobs permanently than men due to the pandemic in China, South Korea, Japan, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Dang & Nguyen, 2020). Table 2 shows that 5.8% of women and 4.8% of men reported losing their job permanently, while roughly equal percentages of women and men (25%) reported losing their job temporarily (Dang & Nguyen, 2020).

[Table 2 here]

Broken down by country, the impact of gender on job loss due to the pandemic are larger in China, Italy, and the United States compared to Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. In regards to losing a job temporarily versus permanently, there appears to be no significant effects of gender on the probability of temporarily losing a job in most countries. However, only in the United States and the United Kingdom are women more likely to lose a job temporarily than men (Dang & Nguyen, 2020).

In Nigeria, women remained unemployed for a longer period of time (about 3.67 months) compared to men (about 2.61 months) after the initial COVID-19 breakout (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). This specifically hurts women because the longer women stay unemployed, the longer it takes and the harder it is for them to reintegrate into the labor force, lowering future prospects of finding work (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). Overall, the employment of women decreased by 8% more than the employment of men during the pandemic (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). In regards to the interesting phenomenon of farming and business, women were 44% less likely than men to engage in business activities during the pandemic, but 52% more likely than men to engage in farming (Hossain & Hossain, 2021). Thus, not only did women experience a significantly greater reduction in employment during COVID-19, but also a large shift from business to agricultural work. This suggests that women in developing countries have lower job security than men. This also hurts the overall level of productivity of women, as women-managed land is typically less productive than land managed by men, indicating lower labor market returns of farming for women in comparison to men, and more generally of farming in comparison to business (Hossain & Hossain, 2021).

Revisiting the case of Sweden, this country exhibited interesting – and seemingly contradictory – evidence regarding the extent of gender-based job-related impact. Figure 1 shows that unemployment risk exists for all wage levels, but lower-paying jobs (signified by lower wage deciles) were at higher unemployment risk (Campa et al., 2021).

[Figure 1 here]

Although Sweden has relatively low gender-based wage inequality, women still tend to be concentrated in lower-paying jobs, suggesting a contributing factor to unemployment of women (Figure 2) (Campa et al., 2021).

[Figure 2 here]

Additionally, most of the heavily impacted occupations in Sweden were female-dominated. According to Table 1, beauticians are 96.7% female, masseurs and massage therapists are 81.2% female, and cabin crew is 78.5% female (Campa et al., 2021). However, it is important to note that although some highly feminized occupations were significantly impacted by unemployment, these occupational fields are relatively small in size in Sweden (Campa et al., 2021). On the other hand, the unemployment risk actually decreased for some occupations, a few of which are female-dominated as well. Some of the notable occupations are clinical and operations managers in healthcare, department managers in elderly care, pediatric nurses (97% women), and anesthesia nurses (74% women) (Campa et al., 2021). Thus, although some female-dominated fields were adversely affected by unemployment, these fields are relatively small, and some larger sectors that are also dominated by women have experienced an increase in the demand for workers (Campa et al., 2021). Thus, Campa et al. (2021) found that women did not suffer higher unemployment rates than men in Sweden and may actually have had a just barely statistically significant lower unemployment risk than men did. From March 2020 to July 2020, the unemployment risk for men was 2.5 percentage points higher, whereas the unemployment risk for women was 0.5 percentage points, or 20% less than the risk for men (Campa et al., 2021).

However, it is important to note that the findings from Sweden may not be representative of the unemployment impacts of women elsewhere in the world, as Sweden took a unique approach in responding to COVID-19. Sweden never enforced a lockdown where people had to stay home from work and school. Since daycare and childcare centers remained open, Swedish families did not have to make significant adjustments to the time they dedicate to childcare, a responsibility that often falls on women (Campa et al., 2021). Additionally, Sweden generally has a high labor force participation rate for women to begin with and works to provide feasible opportunities of combining work and family life. Thus, at least in the case of Sweden, gender did not have a significant impact on unemployment (Campa et al., 2021). Like Sweden, there is also no evidence of unequal impacts of the pandemic on women and men in Germany (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020) or in Italy (Casarico & Lattanzio, 2020).

These findings suggest that the type and/or extent of governmental response to COVID-19 may have influenced the extent to which gender-based employment was affected. Sweden took a relatively minimalist approach in addressing COVID-19 and thus did not have to greatly deviate from its “normal” way of life. Sweden also experienced relatively equal impacts of COVID-19 on the unemployment of both women and men. On the other hand, countries such as the United States, China, and Nigeria more strictly enforced COVID-19 protective measures such as mandatory facemask use, social distancing, travel restrictions, and lockdowns (Dang & Nguyen, 2020; Hossain & Hossain, 2021). These countries also experienced a greater extent of gender inequality in terms of unemployment due to the pandemic. The status of the country as developed or developing may also contribute to these findings, as these countries have different labor participation rates, infection rates, and shares of women in the labor force (Dang & Nguyen, 2020).

4. Results

The findings suggest a general global trend in increasing unemployment rates as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with women being particularly hard-hit. Based on the literature review, the following section suggests several factors that policymakers should take into account when working towards economic recovery, such as a country’s status as developed or developing, type of occupation, and type of unemployment, which will be discussed in the following section. Policymakers should also consider implementing certain standard practices in promoting gender equality on a regular basis, as these types of practices appear to be protective factors against worsening gender inequality during economic downturns.

A comparison of the unemployment rates and types of jobs affected between men and women in developed versus developing countries suggests that the classification of a country as developing has important implications on gender-based employment. As Hossain & Hossain (2021) emphasized, developing countries such as Nigeria are in an especially precarious spot given the lower labor participation rates, inferior and more temporary job types, lack of access to savings and credit, and significant earning gap between men and women that existed even before the pandemic. Thus, when the pandemic took hold, lack of protection against the virus and slow economic recovery rate enhanced the long-term negative outcomes of COVID-19 compared to in developed countries. When working towards economic recovery in developing countries, policymakers must target the root of the turmoil– the preexisting gender inequality– and work toward giving women protected property rights, promote labor reintegration after job loss for women (particularly into the field they were previously working in, as opposed to having to switch to agriculture), and support women’s entry into typically men-dominated fields (such as business).

Developed countries were undoubtedly significantly affected by the pandemic, but in different ways from Nigeria, as they did not necessarily experience gender-based restructuring of the distribution of employees and related effects. Campa et al. (2021) shows that Sweden was able to maintain a state of “normalcy” during the pandemic, did not witness drastically disruptive changes in lifestyle patterns that affected jobs, and experienced a relatively even distribution of negative effects on employment outcomes between men and women. While Sweden’s minimalist approach to COVID-19 may have played a major role in preventing drastic lifestyle changes, this approach was certainly not ideal for every country. It is important to consider Sweden’s preexisting high labor force participation rate for women and the availability of feasible opportunities of combining work and family life. Using Sweden as an example, policymakers in other countries should aim to establish family-friendly measures that allow families to balance work and home life (especially working women, as the shared responsibilities typically fall on them more than men). Implementing such policies would promote gender equality as a part of a country’s regular work culture and may prevent the exacerbation of gender inequalities during economic downturns.

Other important factors to consider for policy making include type of occupation and type of unemployment. As evidenced by the specific job types that were impacted by the pandemic, such as masseurs, cabin crew, beauticians, healthcare workers, and agriculture, policymakers should aim to help women reintegrate into these industries and establish greater job security in the future in the event of another major economic downturn (Campa et al., 2021; Hossain & Hossain, 2021). Since many of these jobs tend to be service-based and require physical proximity, special sanitary precautions may be taken to reduce the risk of laying off such workers if another future public health crisis occurs. In regards to type of unemployment, policies aiming to help women who lost jobs permanently may be more urgent as there are higher rates of women losing jobs permanently compared to men than losing jobs temporarily (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Dang & Nguyen, 2020). Policies facilitating access to education and job training, urging communities to hold networking opportunities and job fairs, and promoting job advertisement on social media may help women diversify their skills and facilitate job match.

5. Conclusions

5.1 Summary and Implications

The purpose of this literature review is to highlight some of the major determinants of occupational segregation during COVID-19 for policymakers, giving them a clear understanding of what factors to consider when formulating policy responses to alleviate the impact of pandemic and take preventative measures against similar future crises. This literature review highlights the increasing unemployment rates that arose as a result of the pandemic, both in developed and developing countries. In both cases, women were disproportionately affected and experienced higher rates of unemployment and difficulty reintegrating into their former jobs, especially since several female-dominated, service-based industries were adversely affected. This is largely attributable to the inability to continue several service-based jobs during the pandemic and the closure of daycare and childcare centers, causing much of the responsibility of childcare to often fall on mothers, who as a result, were more likely to leave their jobs.

To combat this growing gender inequality, economic policymakers must consider a country’s status as developed or developing, type of occupation, and type of unemployment in crafting the appropriate policies to facilitate economic recovery and gender equality. Potential policies worth pursuing include those regarding job security, training, and family-friendly policies that enable a realistic work-home balance. Although this is a holistic overview of global unemployment rates, Sweden and Nigeria provide particular guiding examples that policymakers can look to in regards to developed and developing countries, respectively. Each country responded to COVID-19 differently based on their unique circumstances and faced varying effects as a result.

5.2 Limitations

While this literature review is one of the first in providing a broad overview of the pandemic’s impacts on unemployment, there are a few limitations that must be considered. Firstly, unemployment was measured in different ways in different studies. These numbers were not adjusted before including them in this paper as one purpose of this literature review was to simply outline general trends in unemployment rate globally due to COVID-19. Additionally, although several countries were mentioned in this overview, particular attention was given to Sweden and Nigeria to highlight notable differences between developed and developing countries. However, it is unrealistic to assume that Sweden is representative of all developed countries’ methods of handling gender inequality and COVID-19, and likewise, that Nigeria is representative of all developing countries in this regard. Lastly, this literature review does not advise on specific policies that should be pursued, but rather, simply guiding factors that policymakers should consider.

5.3 Future Directions

For future direction, reports on unemployment rates (particularly meta-analyses conducted with more gathered data) should be standardized such that rates are measured using the same metrics and calculation methods. More developed and developing countries should also be highlighted to compare and contrast gender-based job outcomes, COVID-19 responses, and policy efficacy. Additionally, unemployment in regards to disparities in race, education level, and location (urban, suburban, or rural) may be studied. Lastly, an analysis of changes in the gender wage gap due to COVID-19 may be included, as these have important implications on earnings and retirement pensions.

References

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104245.

Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 26947.

Bächmann, A., Gatermann, D., Kleinert, C., & Leuze, K. (2022). Why do some occupations offer more part-time work than others? Reciprocal dynamics in occupational gender segregation and occupational part-time work in West Germany, 1976–2010. Social Science Research, 104, 102685–102685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102685

Bennett, J. (2021, March 22). Long-term unemployment has risen sharply in U.S. amid the pandemic, especially among Asian Americans. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/11/long-term-unemployment-has-risen-sharply-in-u-s-amid-the-pandemic-especially-among-asian-americans/

Burns, D., & John, M. (2020, December 31). Covid-19 shook, rattled and rolled the global economy in 2020. Reuters. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-economy-yearend-graphic-idUSKBN2950GH

Campa, P., Roine, J., & Stromberg S. (2021). Unemployment inequality in the pandemic: Evidence from Sweden. Covid Economics, 83(2), 1-24.

Casarico, A. & Lattanzio, S. (2020). The heterogeneous effects of COVID-19 on labor market flows: Evidence from administrative data. Covid Economics, 52, 152–174.

Dang, H. & Nguyen, C. (2020) Gender inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic: Income, expenditure, savings, and job loss. World Development, 140, 105296.

Doepke, M., & Tertilt, M. (2016). Families in macroeconomics. Handbook of Macroeconomics, (2).

Hossain, M. & Hossain, M. A. (2021). COVID-19, employment, and gender: Evidence from Nigeria. Covid Economics, 82(23), 70-98.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., & Schalle, J. (2012). Who suffers during recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 27–48.

Sumner, A., Hoy, C., & Ortiz-Juarez, E. (2020). Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty. WIDER Working Paper, 43.

United Nations (UN). (2019). Report of the Secretary-General. Special edition: Progress towards the sustainable development goals. https://undocs.org/E/2019/68

Appendix

Figure 1: Unemployment impact by wage decile in Sweden, (2021).

Table 1: Occupations with the highest unemployment impacts in Sweden (2021).

Figure 2: Share of female workers by wage decile (2021).

Figure 3: Job participation rates of males and females in Nigeria in various occupations (2021).

Table 2: Gender differences in job loss, expected income reduction, weekly expenses, and savings (2020).

Figure 4: Percent of US unemployed out of work for more than 6 months. US workers are 16 years or older, seasonally adjusted. The Great Recession was from December 2007 to June 2009. The COVID-19 recession began in February 2020 (2021).

Figure 5: Global view of unemployment rate during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020).