by Sophia Garbarino, February 9, 2021

The following article is a revised version of the original piece and does not include all photos. The full original article with all accompanying photographs can be viewed by downloading the PDF below (recommended, but viewer discretion advised).

American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe shocked the international art community in 1988 with The Perfect Moment exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in Cincinnati, Ohio. Against politicians’ desires, the CAC decided to display Mapplethorpe’s work even though the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. cancelled the same exhibit only a few months earlier (Tannenbaum). The majority of Mapplethorpe’s photos were labeled obscene and pornographic, leading to criminal charges pressed against the CAC and its director at the time, Dennis Barrie. One of the most shocking was Rosie (1976), a photograph featuring a friend’s three year-old daughter sitting with her legs open, revealing her nude body beneath her dress. The trial took over a year, ending in acquittal and the public display of Mapplethorpe’s work at the CAC in 1990, just over one year after his death in 1989 (Mezibov).

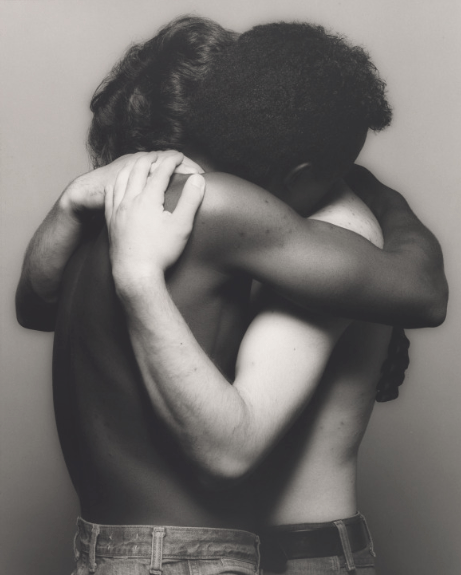

Nude photography was one of Mapplethorpe’s specialties. Several of his portfolios featured the S&M and LGBTQ* communities in New York City, particularly in nude portraits (“Biography”). Many believe his intense focus on the nude body was an expression of his homosexuality. Rosie however, was one of only two photographs of nude children—the other, Jesse McBride (1976), featured a fully nude five year-old boy sitting on a chair. Both photos were taken with the children’s mothers’ permission but still received heavy backlash and criticism for being “pornographic” (Mezibov).

Ultimately, Mapplethorpe’s Rosie (1976) was not meant to be pedophilic, but rather a response to increasing radical American conservatism during the 1970s and 1980s. Its showcasing in The Perfect Moment exhibition (1988) challenged the limits of censorship and artistic freedom, reflecting the growing social phenomenon of hypersexualization that continues to define American media today.

Senator Jesse Helms and Homosexuality

Mapplethorpe lived in the heart of LGBTQ* activism in New New York in the 1970s. It was during this decade that the gay community began seeing representation in mainstream media, including movies that featured gay characters and the establishment of Gay Pride week. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association stopped recognizing homosexuality as a mental illness, and the corporate world started prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination (Rosen). The LGBTQ* community saw tremendous strides in equality and justice advocacy.

It was during this time that Mapplethorpe became an icon for LGBTQ* folks. According to his friend and writer Ingrid Sischy, Mapplethorpe’s works purposefully focused on homosexuality in order to draw attention. His unapologetically direct photographs helped turn homosexuality from a shameful secret into a proud identity (Sischy).

However, the AIDS epidemic soon heightened homophobia in the 1980s. Mapplethorpe heavily focused on black male nudes, a clear expression of his homosexuality, making him a prime target for censorship. Republican Senator Jesse Helms was especially offended by Rosie and hyperfocused on Mapplethorpe’s homosexuality, AIDS-related death, and interracial photographic subjects (Adler, Meyer). In 1989, Helms convinced the deciding congressional committee to pass a bill prohibiting the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) from funding the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), which organized the original Perfect Moment exhibit, for five years (Adler, Tannenbaum). He did so by lying about the photographs he saw firsthand at The Perfect Moment and distributing copies of four of them to the other committee members (Meyer).

At the time, Senator Helms’ arguments reflected those of a growing conservative movement. His outrage about Rosie was less about the photograph itself and more about the artist. Furthermore, his push for censorship was less about Rosie’s exposed body and more about silencing the LGBTQ* community, including proudly gay folks such as Mapplethorpe. In his attempts to “cordon off the visual and symbolic force of homosexuality, to keep it as far as possible from [himself] and the morally upstanding citizens he claim[ed] to represent,” Helms ironically brought even more attention to it (Meyer 134).

Some supported censoring Mapplethorpe’s work by claiming he was a pedophile and child abuser, but neither Jesse nor Rosie recall him as such. As adults, both reflected on their portraits proudly (Adler). As censorship lawyer Edward de Grazia wrote regarding the Mapplethorpe case, “art and child pornography are mutually exclusive… no challenged picture of children having artistic value can constitutionally be branded ‘child pornography’ or ‘obscene’” (de Grazia 50). Though it was ultimately deemed non-pornographic after the Mapplethorpe trial, Rosie was only the beginning of a political push to seize funding from the arts, particularly the radical works such as Mapplethorpe’s, following several rising liberal and conservative movements in the previous decades.

Historical Context: Radical Conservatism and the Sexual Revolution

During the 1970s, the LGBTQ* community became more vocal, allowing gay men such as Mapplethorpe to be more openly accepted in the art world. In response, movements such as the New Right and the Christian Right emerged, led largely by American evangelicals claiming that homosexuality was morally sinful (“The New Right”). Mapplethorpe’s very existence contradicted traditional conservative values, and he could never align with socially-accepted heteronormative culture.

In fact, the Rosie controversy emerged during a new wave of conservative outrage that began a few years earlier in 1987, when Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ was awarded $15,000 by the partially NEA-funded Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (Meyer). Along with many other Republican Christians, Senator Helms was deeply offended and embraced the opportunity to denounce another artist who defied traditional conservative values when The Perfect Moment debuted in 1988. At that point, Helms’ focus shifted from Serrano’s critique of religion to Mapplethorpe’s expressions of homosexuality, repeatedly calling his photographs “sick” (Meyer 137). In doing so, Helms used the art as a larger metaphor for homosexuality and AIDS, which he believed were plaguing and contaminating Christian-American society.

As a gay man, Mapplethorpe was not sexually attracted to females at all, so it would have been much easier for Helms to use Jesse McBride rather than Rosie in his rhetoric. It was the ongoing sexual revolution, which also contributed to the rise of far-right conservatism, that put Rosie in the spotlight instead. Rosie, then, can be interpreted as Mapplethorpe’s way of challenging traditional ideologies and aligning with the sexual liberation movement. Where he saw an innocent child, many conservatives such as Senator Helms saw the bare sexuality of a young girl. Movements such as the New Right could not view her as anything other than sexual with her genitalia exposed. Therefore, it was not Mapplethorpe who sexualized the child but the audience who saw her, revealing a culture deeply rooted in traditional domestic roles and gender spheres.

The 1960s and 1970s saw a rapid increase in women’s and sexual liberation. Nonheterosexual sex was brought to national attention as well, especially after the Stonewall Riots in 1969 (Kohn). Much of Mapplethorpe’s work reflected this new spotlight. Rosie, though, was unlike his trademark photographs of an interracial S&M community, yet it still gained significantly more attention. Despite the portrait subject being a White child, Rosie was one of the four photographs that Senator Helms distributed to his fellow Congressmen and Senators. The others were Mark Stevens (Mr. 10½) (1976), Man in Polyester Suit (1980), and Jesse McBride (Meyer). There were several other photos of naked men in The Perfect Moment, many considered far more pornographic than Rosie and Jesse McBride could ever be, but Rosie was not chosen by mistake. She reflected a different, but not unrelated, threat to Christian-American tradition: women’s liberation.

After the birth control pill hit the market in 1960, sexuality and sexual expression were no longer taboo subjects. Rates of premarital sex increased significantly while books such as Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex normalized conversation about sex (Kohn). For many, Rosie represented a new generation of sexually-liberated women. For conservatives like Senator Helms, this was an intolerable break from traditional gender roles, where men and women had defined, separate roles in society. The New Right movement believed the sexual revolution was destroying the American family structure, leading little girls like Rosie from domesticity to radicalism (“The New Right”). Rosie, then, was the epitome of everything wrong with women’s liberation for Helms. In distributing her photograph, he attempted to defy the new wave of feminism.

Censorship and Artistic Freedom

However, despite its many controversies, the Mapplethorpe censorship case was most defiant of artistic freedom. Following the case, American art critic Robert Storr wrote that “there are no ‘laws of decency’; certainly none that have any juridical standing with respect to art” (Storr 13). He further argued that censorship itself is the manifestation of widespread mistrust of the public’s ability to draw their own conclusions. In a nation founded on freedom of speech and expression, art essayists like Hilton Kramer, who deeply criticized Mapplethorpe’s work, and politicians like Helms ironically believed that common people should not and could not discern what was acceptable, particularly regarding art (Storr). Helms and Kramer used censorship to impose their own beliefs onto the general public, serving as a microcosm of strong conservative attempts to minimize the voices of non-traditional values.

When such defiances of conservatism emerged, they were immortalized in the form of art through Mapplethorpe and other “radical” artists like Serrano. In the heat of America’s changing society, Rosie became a monumental representation of true freedom: freedom of artistic expression, freedom of sexual expression, and the freedom of perspective. Politicians, however, disagreed over what freedoms should receive public funding. Helms and his fellow White Christian American conservatives believed that the NEA should not fund art that offended them based on “their assault on social constructions of sexuality, race, and spirituality” (Atkins 33). Once again, the majority group was attempting to impose their beliefs on the rest of society, a perfect example of censorship at its core.

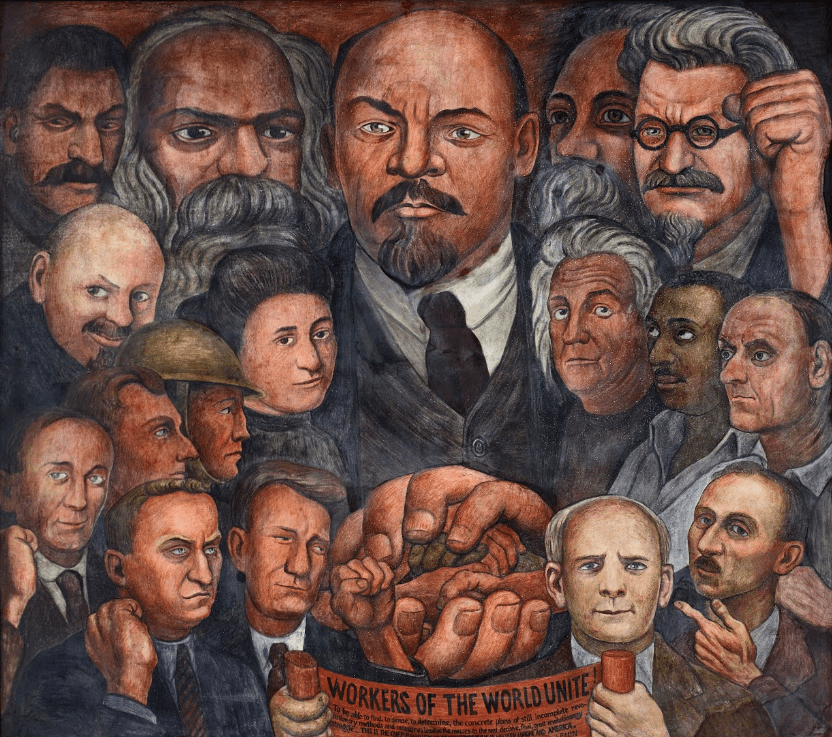

Mapplethorpe’s case was significant but not the first. Works by LGBTQ* folks, people of color, and those with “dangerous” political views have been consistently marginalized. For example, Diego Rivera’s Portrait of America mural at Rockefeller Center was destroyed in 1933 because its center featured Vladimir “Lenin” Ulyanov, former leader of the communist Soviet Union (Atkins). In 1934, Paul Cadmus’ The Fleet’s In was removed from the Corcoran Gallery of Art—the same gallery that cancelled The Perfect Moment in 1988—because the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration requested it (Atkins). This was only a small part of FDR’s anti-gay legacy: during his time as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, FDR helped run a sting operation in Newport, Rhode Island in 1919, resulting in the arrest of over 20 Navy sailors for homosexual activity (Loughery). In 1981, after strong advocacy from Hilton Kramer and other conservative critics, the NEA stopped funding individual art critics because many of them were leftist (Atkins). Clearly, the Mapplethorpe case followed decades of conservative attacks on art.

Hypersexualization

Some believe the most pressing issues surrounding Rosie were Rosie’s age and exposed body. There were certainly multiple other artists photographing naked women at the time, like Don Herron and his Tub Shots series, who received little criticism for the nudity. In fact, nudity itself has never been an issue in art; some of the most famous and public classical works portray naked Romans, Greek gods, and biblical figures, like Michelangelo’s David and Sistine Chapel ceiling. In fact, nude boys were not an issue either, as seen in works like Thomas Eakins’s Boy nude at edge of river (c. 1882) and John Singer Sargent’s A Nude Boy on a Beach (1925).

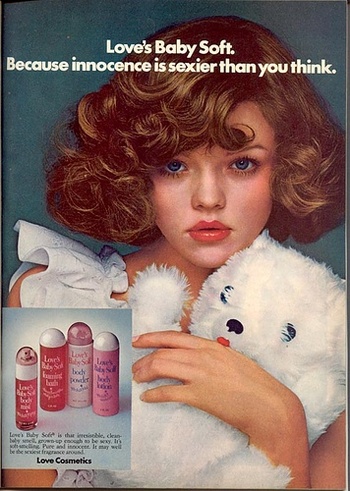

The fact that Rosie was a girl was not the most significant factor either. During the 1970s, when the Rosie photograph was taken, the United States saw a rapid increase in explicit advertisements, particularly those with women only partially dressed or in full nude. One 1993 study revealed that the number of purely decorative female roles in ads increased from 54 percent to 73 percent from 1959 to 1989 (Busby and Leichty). A 1997 study found that over a 40-year period, 1.5 percent of popular magazine ads portrayed children in a sexual way, and of those ads, 85 percent depicted sexualized girls, with the number increasing over time (O’Donohue et. al). Even in the 1970s and 1980s, the sexualization of young girls was certainly nothing new. Advertising industries had been doing this for decades before the Rosie controversy started in 1988. In fact, they still do.

The hypersexualization of both women and children in the media is quite common now. As National Women’s Hall of Fame activist Dr. Jean Kilbourne reveals in So Sexy So Soon, corporations use sex and sexiness to advertise to children at increasingly younger ages—and they are alarmingly successful. Dangerously unhealthy standards of beauty define sexiness as the most important aspect of a woman’s identity and value. The sexual liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s has turned into a hypersexualized culture, where children as young as Rosie are exposed to sex in songs, TV shows, advertisements, and social media (Kilbourne and Levin). Like the conservatives’ reaction to Rosie in 1988, young girls are now seen in a sexual way before they are seen as simply children.

Therefore, like the basis of Helms’ original arguments, the outrage and controversy surrounding Rosie was less about the photograph itself and more about the artist and what the artist represented. Mapplethorpe’s identity and lifestyle contradicted many traditional conservative values: he was homosexual, engaged in S&M, photographed interracial couples, and eventually died of AIDS. Rosie herself said she did not view her portrait as pornographic and could not understand why others thought it was. In fact, in a 1996 interview with The Independent, Rosie recalled her mother making her put on a dress just before the photo was taken, and immediately after, she took the dress off. Ironically, she noted that “if it had been a small [nude] boy, maybe this furore would be justified; Robert [Mapplethorpe] wasn’t interested in girls anyway” (Rickey). Jesse McBride, which is exactly that, received even less backlash than Rosie.

Helms, then, used Rosie against Mapplethorpe not because he thought it was pornographic, but because of all Mapplethorpe’s works, Rosie garnered the most conservative support for censorship. He could easily use the classic damsel in distress situation by painting Rosie as a helpless little White girl in need of protection from a dangerous gay man, with emphasis on Mapplethorpe’s homosexuality. It wasn’t Rosie’s age, nor her exposed body, that angered Helms: it was Mapplethorpe.

Final Notes

The Rosie controversy was just as relevant in 1988 as it is now. It continues to pose crucial questions, challenging the boundaries of art and the limits of censorship while highlighting the marginalization of LGBTQ* art, societal resistance to change, and hypersexualization of women and children. Ultimately, Rosie was not the creator of such outrage and conservative criticism, but the vessel exploited by powerful politicians to further their own agendas against Mapplethorpe and other LGBTQ* folks. The Mapplethorpe trial surrounding Rosie was the culmination of decades of liberal movements—including women’s liberation, the sexual revolution, and increasing attention to LGBTQ* voices—and the conservative responses to them. Despite the continuous controversy, critics consider Mapplethorpe, rightfully so, as one of the most influential American artists in the twentieth century. Rosie was last on public display in 2017 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Works Cited

Adler, Amy. “The Shifting Law of Sexual Speech: Rethinking Robert Mapplethorpe.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 2020, no. 1, 2020, chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2020/iss1/2.

Atkins, Robert. “A Censorship Timeline.” Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 3, 1991, pp. 33–37. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/777212. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.

“Biography.” Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, www.mapplethorpe.org/biography/. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Busby, Linda, and Greg Leichty. “Feminism and Advertising in Traditional and Nontraditional Women’s Magazines 1950s-1980s.” Journalism Quarterly, vol. 70, no. 2, 1993, pp. 247–264. SAGE Journals, doi.org/10.1177/107769909307000202. Accessed 27 Jan. 2021.

Cadmus, Paul. The Fleet’s In!. 1934. United States Navy, Washington, D.C. Naval History and Heritage Command, www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/art/travelling-exhibits/paul-cadmus.html. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Capps, Kriston. “Jesse Helms: The Intimidation of Art and the Art of Intimidation.” Huffington Post, 15 July 2008, www.huffpost.com/entry/jesse-helms-the-intimidat_b_112874. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

“Cuties.” Wikipedia, 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuties. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Davies, Diana. “Men holding Christopher Street Liberation Day banner.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1970, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/91433901-5e24-aece-e040-e00a18066e82. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

de Grazia, Deward. “The Big Chill: Censorship and the Law.” Aperture, 5 May 1990, pp. 50–51. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24472936. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.

Eakins, Thomas. Boy nude at edge of river. c. 1882. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. PAFA, www.pafa.org/museum/collection/item/boy-nude-edge-river. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Herron, Don. “Paula Sequeira.” Swann Galleries, 1978, catalogue.swanngalleries.com/Lots/auction-lot/DON-HERRON-(1941-2012)–Suite-of-11-photographs-from-Tub-Sho?saleno=2514&lotNo=184&refNo=756720. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

“Jesse Helms.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/H000463. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Kilbourne, Jean, and Diane Levin. So Sexy So Soon: The New Sexualized Childhood, and What Parents Can Do to Protect Their Kids. Ballantine, 2008.

Kohn, Sally. “The sex freak-out of the 1970s.” CNN, 21 July 2015, www.cnn.com/2015/07/21/opinions/kohn-seventies-sexual-revolution/index.html. Accessed 27 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Ajitto. 1981. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City. Guggenheim, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/2701. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. LACMA Collections, collections.lacma.org/node/2155762. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Dan. S. 1980. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/255901/robert-mapplethorpe-dan-s-american-negative-1980-print-2011/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Derrick Cross. 1982. Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, www.mapplethorpe.org/portfolios/male-nudes/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Embrace. 1982. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/256224/robert-mapplethorpe-embrace-american-negative-1982-print-1996/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Honey. 1976. Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/robert-honey-ar00157. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Honey and Rosie. 1976. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. LACMA Collections, collections.lacma.org/node/2233535. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Jesse McBride. 1976. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. LACMA Collections, collections.lacma.org/node/2233522. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Ken Moody and Robert Sherman. 1984. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/2740. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Man in Polyester Suit. 1980. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/254454/robert-mapplethorpe-man-in-polyester-suit-american-negative-1980-print-1981/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Mark Stevens (Mr. 10½). 1976. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/254447/robert-mapplethorpe-mark-stevens-mr-10-12-american-1976/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Patti Smith. 1976. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Met Museum, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/266975. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Phillip. 1979. Modern Museum of Art, New York City. MoMA, www.moma.org/collection/works/199945. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Phillip Prioleau. 1979. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/255738/robert-mapplethorpe-phillip-prioleau-american-1979/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Rosie. 1976. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. LACMA Collections, collections.lacma.org/node/2233440. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Self Portrait. 1980. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/255800/robert-mapplethorpe-self-portrait-american-negative-1980-print-1999/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Self Portrait. 1980. Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/robert-self-portrait-al00388. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Self Portrait. 1988. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/5354. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Tennant Twins. 1975. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/255477/robert-mapplethorpe-tennant-twins-american-1975/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Thomas. 1987. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/5353. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Meyer, Richard. “The Jesse Helms Theory of Art.” October, vol. 104, 2003, pp. 131–148. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3397585. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.

Mezibov, Marc. “The Mapplethorpe Obscenity Trial.” Litigation, vol. 18, no. 4, 1992, pp. 12–15, 71. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/29759554. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.

“The New Right.” ushistory.org, www.ushistory.org/us/58e.asp. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

O’Donohue, William, et al. “Children as Sexual Objects: Historial and Gender Trends in Magazines.” Sexual Abuse, vol. 9, no. 4, 1997, pp. 291–301. SAGE Journals, doi.org/10.1177%2F107906329700900403. Accessed 27 Jan. 2021.

Rickey, Melanie. “Revealed (again): Mapplethorpe’s model.” The Independent, 14 Sept. 1996, www.independent.co.uk/news/revealed-again-mapplethorpe-s-model-1363318.html. Accessed 27 Jan. 2021.

Rivera, Diego. Proletarian Unity from Portrait of America. 1933. Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya. Google Arts & Culture, artsandculture.google.com/asset/proletarian-unity-diego-rivera/1QGr_VcJ142Tpw?hl=en. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

“Robert Mapplethorpe.” Gladstone Gallery, 2018, www.gladstonegallery.com/exhibition/296/robert-mapplethorpe/installation-views. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Rosen, Rebecca. “A Glimpse Into 1970s Gay Activism.” The Atlantic, 26 Feb. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/02/a-glimpse-into-1970s-gay-activism/284077/.

Sargent, John Singer. A Nude Boy on a Beach. 1925. Tate. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sargent-a-nude-boy-on-a-beach-t03927. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Serrano, Andres. “Immersion (Piss Christ).” TIME 100 Photos, 1987, 100photos.time.com/photos/andres-serrano-piss-christ. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Sharp, Gwen. “‘Because Innocence is Sexier than You Think’: Vintage Ads.” The Society Pages, 13 Nov. 2008, thesocietypages.org/socimages/2008/11/13/because-innocence-is-sexier-than-you-think-vintage-ads/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2021.

Sischy, Ingrid. “White and Black.” The New Yorker, 6 Nov. 1989, www.newyorker.com/magazine/1989/11/13/white-and-black. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.

Storr, Robert. “Art, Censorship, and the First Amendment: This Is Not a Test.” Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 3, 1991, pp. 12–28. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/777210. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.

Tannenbaum, Judith. “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Philadelphia Story.” Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 4, 1991, pp. 71–76. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/777326. Accessed 26 Jan. 2021.